[By Bhanu Dhamija]

[A version of this article was published under the heading ‘New Parliament. Old Governance’ on The Quint website on 10 July 2024.]

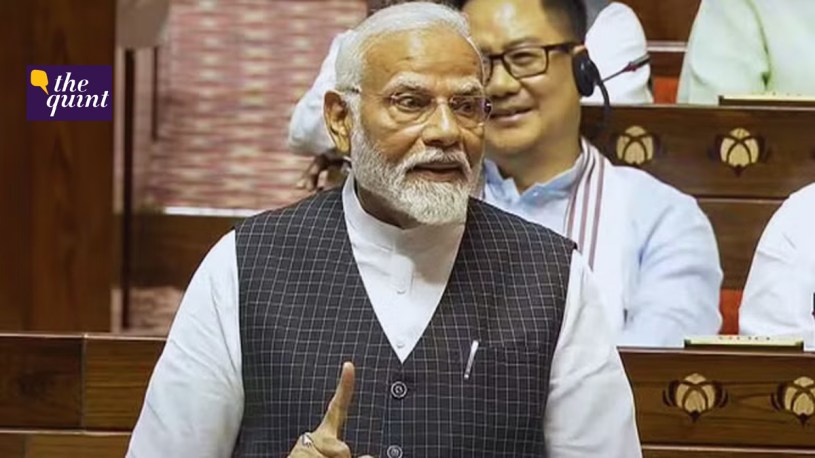

India’s recent parliamentary elections were hailed as having saved its democracy. Many Indians critical of Prime Minister Modi’s authoritarian style of governance believed that since the BJP lost its outright majority, he would be more restrained and accommodating of other parties. But within days under the new political configuration, parliamentary proceedings and government actions show that India continues to be an “Electoral Autocracy” where elections are held but governance is autocratic. That label was assigned to India in 2021 by Sweden’s V-Dem Institute.

In Parliament, Modi government’s new coalition partners, the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) and Janata Dal United (JDU), with 28 seats between them, have squarely fallen in line with the BJP. There was not a peep from them when a staunch BJP leader, Om Birla, was reappointed Speaker of the Lok Sabha. They were also in lockstep when Birla decided to expunge from House records the Leader of Opposition Rahul Gandhi’s remarks attacking the BJP’s Hindutva agenda. Similar actions were taken against the opposition leaders in the Rajya Sabha, which was unaffected by the recent elections and continues as before under the chairmanship of BJP loyalist Vice President Dhankhar.

The new Modi government is no different from the last one. Loyalists have been assigned to key portfolios, and there is no change in the top four ministries. Home stays with Amit Shah, Finance with Nirmala Sitharaman, External Affairs with S. Jaishankar and Defense with Rajnath Singh. Eight Cabinet committees were reconstituted, but Modi remains at the helm of nearly all.

If Modi critics expected a humbled man after the elections, there are no such signs. “Modi is still strong,” he declared in a two-hour speech in Parliament last week. “I want to assure all Indian people that Modi is not one to be scared and nor will be his government.”

Such bluster is remarkable given that the recent election results were seen around the globe as a serious blow to Modi’s reputation. Not only did his party lose 92 of its 303 Lok Sabha seats, but the verdict was a personal defeat because the entire BJP campaign was built around him. The elections also revived a dying opposition under a brand-new alliance led by the Congress Party’s Rahul Gandhi, Modi’s main rival.

In India, good election results don’t necessarily translate into good governance, because our system of government is inherently authoritarian.

The results gave Modi critics hope because they were an impressive display of Indian democracy’s pluralism and forced him to form a coalition. His BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government now depends on support from 14 different parties, most with only one or two parliamentary seats. TDP and JDU, both regional parties, are the two largest partners.

But in India, good election results don’t necessarily translate into good governance, because our system of government is inherently authoritarian. Unlike the U.S. Presidential system, India’s Parliamentary system doesn’t separate executive and legislative powers, or give state and local governments independent control, or allow Members of Parliament to vote against their parties. Instead, it makes the Prime Minister all-powerful, free to act arbitrarily with laws, investigative agencies, party apparatus, taxpayer money, and so on. India has seen all-powerful PMs before in Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi.

An all-powerful Prime Minister cannot be restrained by a coalition, especially when the coalition partners are as small and regional as the NDA. Both TDP and JDU are interested only in securing money and support for their regional aspirations. They are not likely to wrestle with Modi’s national agenda or functioning style. Nor are they in any position to threaten the coalition, for they can be replaced given the BJP’s vast resources, control over investigative agencies, and experience in persuading MPs to switch parties.

So, the authoritarianism in India continues, as was evident in Parliament last week. Unlike the U.S. House of Representatives, where members elect the Speaker in fiercely contested ballots, the Lok Sabha Speaker’s appointment is controlled by the Prime Minister. Once elected, a Speaker is under no risk of losing the position as long as he continues to do the PM’s bidding. By contrast, in a recent episode in the U.S. House, it took Kevin McCarthy 15 ballots to get elected as Speaker, and he was kicked out of office in less than nine months by members of his own party.

India’s pliable Speaker, controlled by a party leader and Prime Minister, acts in a partisan way with impunity. He suspends MPs, expunges their comments, shuts down debate, and dissolves the assembly, all to please his master.

In expunging Rahul Gandhi’s remarks, Birla’s partisanship was on full display. He ordered a wholesale deletion of an opposition leader’s attack on the ruling party’s policies and ideology. The Lok Sabha’s Rule 380, which gives the Speaker the authority to do so, is nothing but an authoritarian tool at the disposal of the ruling party. It allows the Speaker, a ruling party member, total discretion without due process or remedy. In the U.S. House, by contrast, there is “mechanism” for deleting a member’s disorderly or unparliamentary remarks. Another member must make a formal demand; the member alleged can withdraw the remarks; the Speaker can consult the House Parliamentarian; and if the remarks are deleted there is a process of appeal. As a result, of the 170 times the rule was invoked in a recent 50-year period, the U.S. Speaker ordered deletion in only 25 instances. In nearly every case, it was because the member engaged in a personal attack on another member.

If India truly wishes a Parliament that works, and governance that is less autocratic, it must reduce the concentration of powers in the Prime Minister’s Office. Just lecturing a PM or a Speaker to behave more moderately and in a less partisan way is not likely to deliver results.